23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943

The Battle of Stalingrad was a major battle fought on the Eastern Front of World War II between Nazi Germany and its allies against the Soviet Union for the city of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) in southern Russia.

Staggering 2 million military and civilian casualties result from fierce close-quarters fighting and indiscriminate air bombings of the city. The 5-month-long bloodbath ended with the rout of six field armies of German Army Group B, including the complete encirclement and destruction of the German’s 6th Army and a corps of its 4th Panzer Army. This catastrophic defeat led to the collapse of the German Army on the Eastern Front and, ultimately, their defeat in 1945.

The importance of the battle for Stalingrad

After the failure in the in the Autumn of 1941, the German Army had enough time to rest and regroup since the Eastern Front was relatively quiet during the Winter of 1942. Aware of the dwindling oil supplies of their war machine, the German High Command was preparing for another major offensive in the Spring of 1942.

The Operation’s “Fall Blau” (Case Blue) objectives were to quickly secure the oil fields while simultaneously diminishing Stalingrad’s industrial capacity, where a significant quantity of armaments was produced for the Soviet Army. Additionally, any attempt at capturing the city would tie up a considerable number of Soviet Forces around Stalingrad, thus covering the north flank of the German Army in the Caucasus while disrupting the logistical lines running along the Volga River.

German leader wanted to capture the city and use it as a tremendous personal and propaganda victory for the German Reich since the city bore the name of the Soviet leader, . Securing the city would significantly boost the morale of the German Army while breaking the morale of the Soviet people and their will to continue fighting.

Prelude to the attack

On the Eastern Front, Nazi Germany captured vast expanses of Soviet territory, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic Republics. The front was more than 1,600 kilometers long, stretching from Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the north to Rostov-on-Don in the south. Three German Armies fighting on the Eastern Front were rested and re-equipped for the upcoming planned offensives.

In the West, German forces held firm control over most of Europe, securing the beaches of the Atlantic Ocean with its famous, impenetrable “Atlantic Wall.” The German Navy had been fighting successfully in the Atlantic, disrupting supply lines between the US and Europe, sinking supply convoys with the deadly use of their U-boats organized in so-called “wolf packs.”

In North Africa, Germans had captured Tobruk in Libya and pursued retreating British forces all the way to El-Alamein in Egypt, where they successfully defended the city and stopped the Germans’ advance.

The Soviets had suffered heavy losses, both in manpower and armament, in the battle for Moscow, which made them incapable of conducting any offensives in the Winter of 1942. Soviet Command concentrated most of its forces around Moscow, preparing for another German push in central Russia.

The plan of the attack on Stalingrad

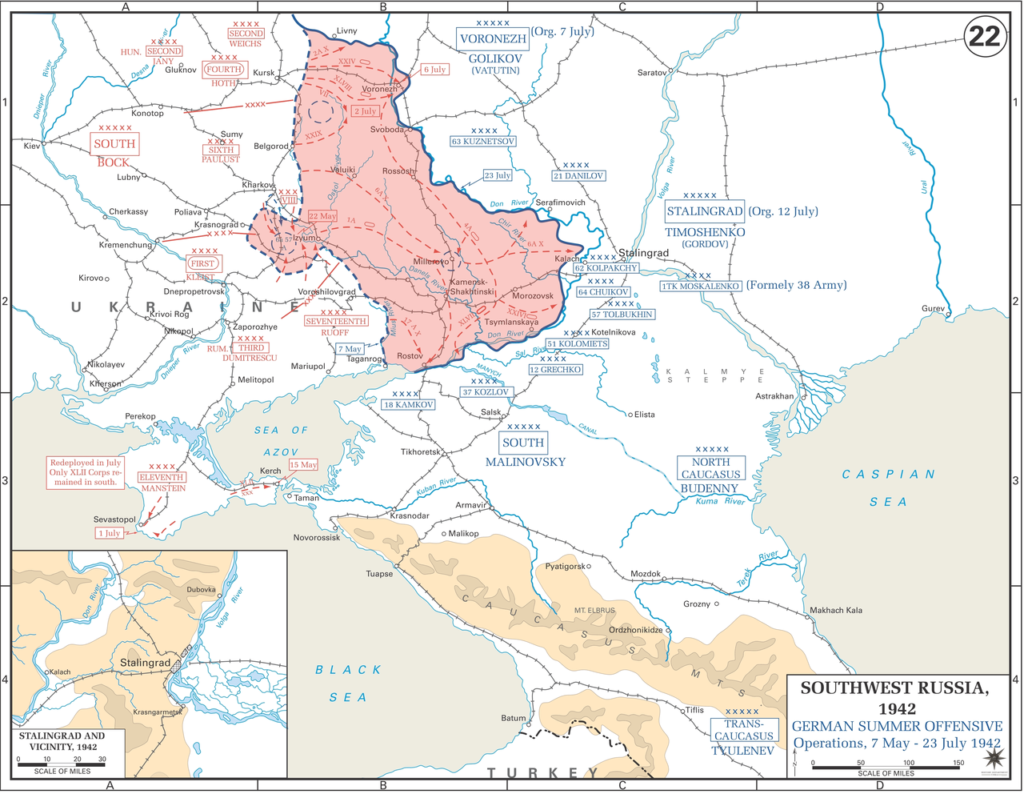

The initial plan of Operation “Fall Blau” was to secure oil fields in the Caucasus and reach Baku quickly. The execution of the objectives was tasked to the Army Group South, which included the 6th, 17th, 4th Panzer, and 1st Panzer Armies already stationed in Ukraine.

However, Hitler changed the initial plan and ordered Army Group South to be split into Army Group South A under the command of and Army Group South B under the command of . Army Group A would continue with the original plan and spearhead the attack in the Caucasus, while Army Group B would advance eastwards towards Volga River and Stalingrad. The split of the forces proved to be quite a challenge for the German logistical system since it could not supply both advancing armies simultaneously. It was also a strategic problem because advancing troops could not efficiently support each other if needed. It also lessened the pressure on the Soviet armies already engaged in fighting, enabling them to escape the encirclement and retreat to new defensive lines.

German High Command planned to start the Operation in May of 1942. Still, the attack date had to be postponed several times due to the delays in ending the siege of Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula, where several German and Romanian troops were fighting encircled Soviet troops.

The start of the offensive

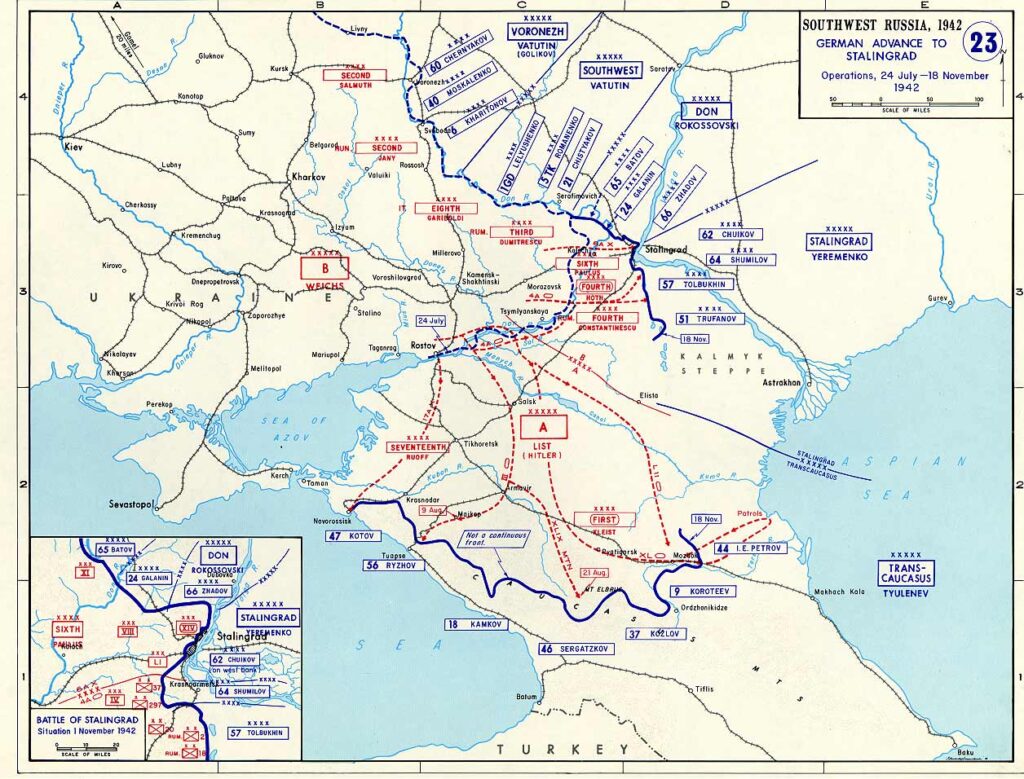

On 28th June 1942, Operation „Fall Blau” officially started, with a massive attack of both German Armies through the Russian steppes. Facing the German onslaught, Soviet defenders could not hold their lines and began to retreat eastwards. Soon after, two major pockets of Soviet troops were formed – one northeast of Kharkiv (destroyed on the 2nd of July 1942) and the second around Millerovo (destroyed a week later). On the 5th of July, the German 4th Panzer Army attacked and captured Voronezh with the help of the Hungarian 2nd Army.

Seeing that the offensive was going better than expected, Hitler changed his plans and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to join Army Group South A in the push toward the Caucasus. This resulted in a massive roadblock when the 4th Panzer Army and 1st Panzer Armies choked the roads, which postponed the German advance. Consequently, Hitler changed his plans again and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to return to their initial plan of attacking Stalingrad.

German troops had reached the Don River by the end of July but did not pursue the Soviets across. Especially fierce fighting broke out west of Kalach-on-Don, where both armies suffered heavy losses in material and manpower. On the southern flank, Army Group South A was nearing the city of Rostov-on-Don as the last major obstacle on their way to the Caucasus.

German High Command tasked their allies (Hungarian, Romanian, and Italian armies) to secure the flanks of the advancing German troops since they were less experienced and poorly equipped to be involved in heavy fighting with the Soviets. Also, the German High Command did not hold them in high regard, often accusing them of low morale and less than capable command structure.

On 20th August, Germans had established bridgeheads across the Don River, with the 6th Army flanking Stalingrad from the north. The 4th Panzer Army had turned northwards to attack the city from the south and block the Soviet retreat.

Attack on Stalingrad

On 23rd August, the 6th German Army reached the outskirts of Stalingrad, pursuing the 62nd and 64th Soviet Army, which had fallen into the city itself. Soviet defense plan had lied on, along with fighting inside the city, putting constant pressure on the German north flank, and committing several armies in badly coordinated and poorly planned attacks on German positions. Especially heavy fighting was around Kotluban, northwest of Stalingrad. Although the Soviets suffered enormous casualties (around 200,000), they did slow the German assault on the city by splitting the German forces in two – one had to fight in the city, and the other had to defend the north flank.

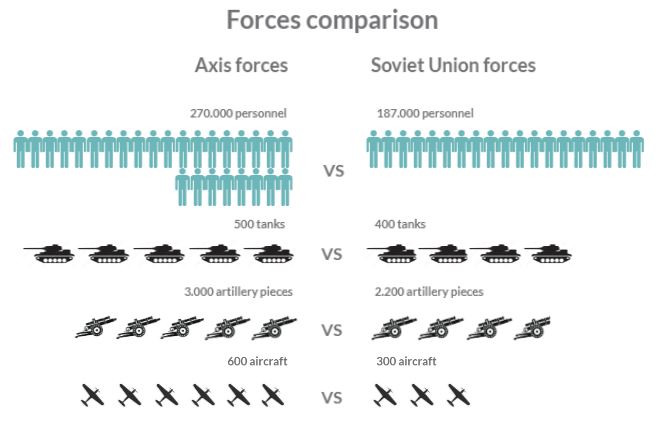

German forces in and around Stalingrad consisted of approximately 270,000 personnel, 3,000 artillery pieces, 500 tanks, and 600 aircraft facing the Soviet troops of around 187,000 personnel, 2.200 artillery pieces, 400 tanks, and 300 aircraft. Encouraged by their high morale and superior firepower, Germans expected to crush the opposition easily, but the constant flow of Soviet reinforcements presented a significant problem since all captured ground had to be defended almost immediately against relentless Soviet counterattacks.

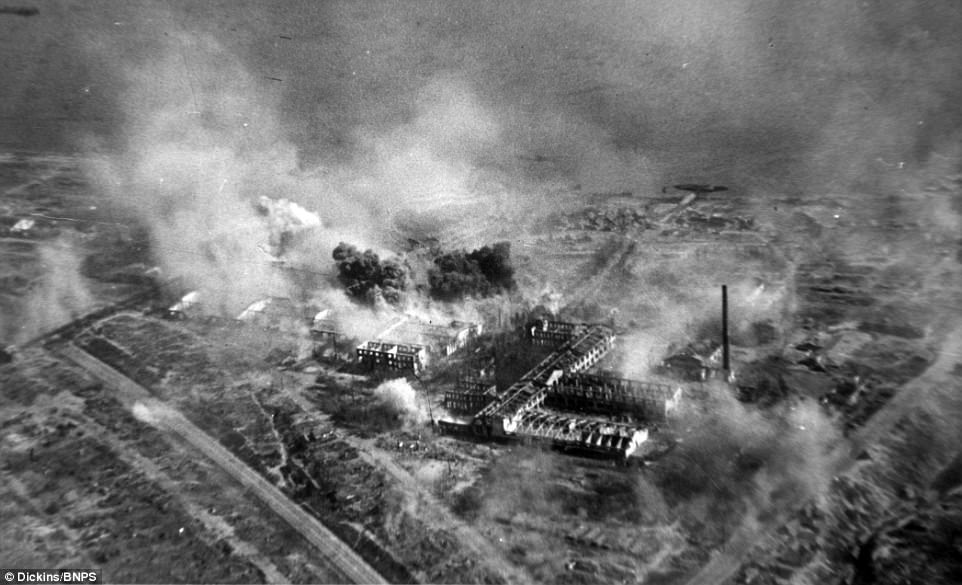

The Luftwaffe raids

The initial attack on the city started with a ferocious bombing by the Luftwaffe, with some 1,000 tons of bombs dropped on the city in 48 hours. At least 90% of the city’s housing was obliterated, and much of the city was smashed to rubble, although some factories remained operational. The famous Stalingrad Tractor Factory continued producing until Germans burst into the plant.

Between the 23rd and 26th of August, the Luftwaffe conducted ferocious and unselective bombardment, resulting in around 40,000 casualties. Enormous casualties were a direct effect of Stalin’s order not to evacuate the citizens from the city to encourage greater resistance from the city’s defenders. The Soviet Air Force (the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS)) was no match for the Germans in the number and quality of airplanes. Although they received constant aerial reinforcements around the city, they suffered appalling losses, resulting in Germans having total control of the skies over Stalingrad.

Defense of Stalingrad

Seeing that the German advance could not be stopped by the troops stationed in and around Stalingrad, Stalin issued orders to rush all available units to the east bank of Volga, some from as far as Siberia. Transporting troops across the Volga was quite a logistical problem for the Soviets since river ferries were easy pickings for the Luftwaffe, while precise German artillery strikes easily targeted slow-moving barges.

The initial defense of the city was tasked with the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment, made up of young female volunteers who had no training in engaging ground targets. Despite having no support from other units, they held Gumrak airport northwest of the city and managed to destroy 83 tanks and 15 vehicles carrying infantry, as well as neutralize over three battalions of enemy assault infantry.

The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Narodny komissariat vnnutrenih del (NKVD)) was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union. Established in 1917, it was tasked with conducting regular police work and overseeing the country’s prison and labor camps. At the beginning of the 1930s, it was given a monopoly over law enforcement activities. It was known for mass extrajudicial executions of citizens and the administration of the Gulag system of forced labor camps. Their agents were responsible for the repression of the wealthier citizens, as well as protecting the Soviet borders and espionage. The NKVD initially organized the “Worker’s militias” to defend the city. These militias were composed of civilians not directly involved in the war production for immediate use in the battle. They were often sent into the carnage without rifles and with only a handful of bullets, expecting to capture enemy rifles or retrieve ones from their dead comrades. Students from a local technical university formed “tank destroyer” units, who managed to assemble tanks from leftover parts at the tractor factory, often driving them to the battle straight from the production lines.

By the end of August, the Soviets were pushed into the inner defensive ring around the city, with Germans flanking from the north and south flanks. On the 2nd of September, the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army linked near Jablotchni. By then, the Soviets had only one way to reinforce and supply their forces in the city – crossing the Volga under constant bombing and bombardment by the Luftwaffe and German artillery.

Soviet counterattacks

The Soviets had attempted numerous counter-offensives to lessen the pressure on the city. On the 5th of September, the 24th and 66th Armies launched a massive attack against the 14th Panzer Corps but were repelled when the Luftwaffe attacked exposed Soviet artillery positions and defensive lines. On the 18th of September, the 1st Guards and 24th Army launched an offensive against the 8th German Army Corps at Kotluban, but Stuka dive bombers helped repel the offensive by destroying 41 tanks of the 106 knocked out that day, while 77 Soviet aircraft were destroyed by German fighter planes.

September city battles

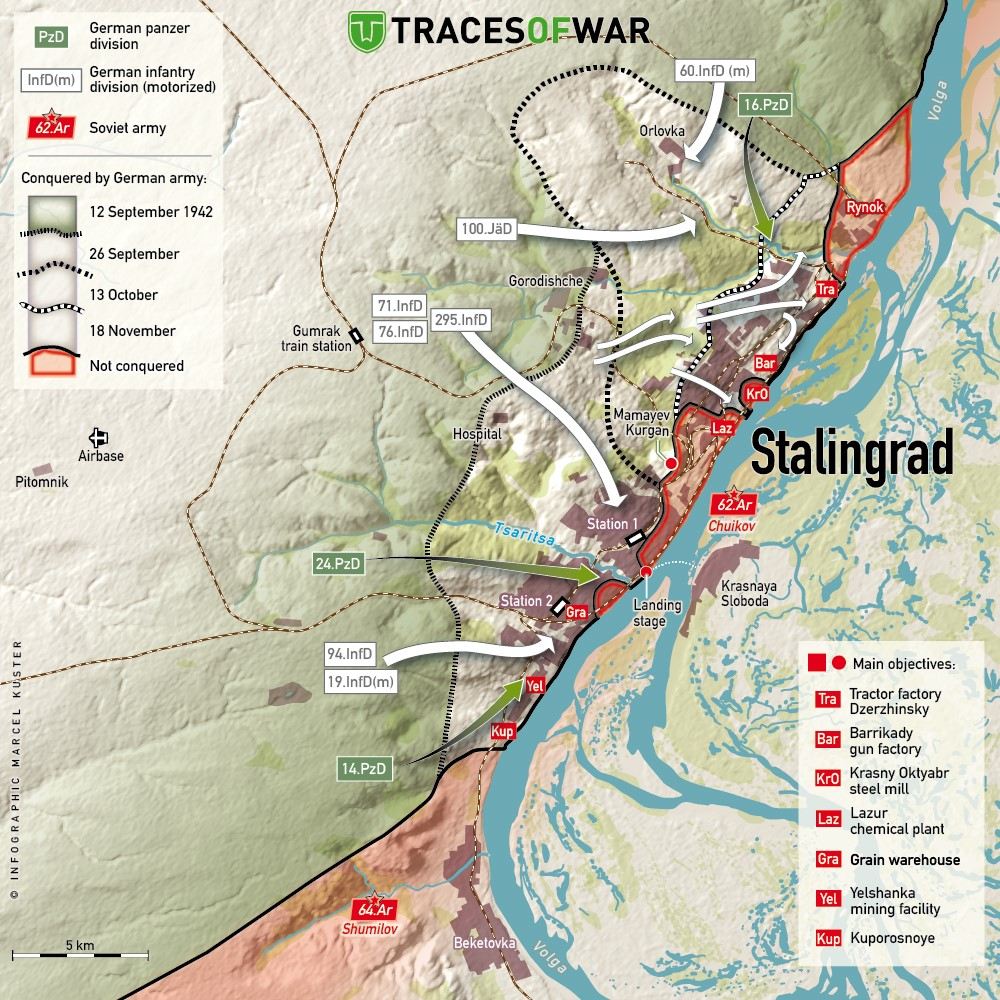

By the 12th of September, the fighting had moved inside the city with ferocious close-quarters combat for every street, factory, house, and even the sewers. The city’s ruins offered perfect positions for ambushes and strong points often successfully held by at most 10-man units.

The German military doctrine of combined arms was less effective inside the city – tanks were easily ambushed and knocked out by anti-tank units, artillery was less effective due to the Soviet tactic of keeping their soldiers as close to German positions as possible, and aircraft had already reduced the city to rubble which made fighting in the city even harder for the attackers. Soviet defenders tried to hold their ground for as long as possible, fighting to the last man. They were constantly reinforced by fresh troops, which enabled them to try to re-take lost positions almost immediately.

On the 14th of September, the 51st Army Corps’ 259th Infantry Division attacked Mamayev Kurgan Hill, while the 71st attacked the central rail station with the plan to advance to the main landing stage on the Volga. The attacks were relatively successful, initially taking both positions, but fierce counterattacks by the Soviets managed to retake them with huge losses.

Heavy fighting occurred in the southern part of Stalingrad, where fifty Soviet defenders held the giant grain elevator for five days but were eventually overwhelmed when they ran out of ammunition and water. During the retreat, they burned large amounts of grain to deny the enemy food.

In another part of the city, a Soviet platoon under the command of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov held a four-story building that oversaw a square 300 meters from the riverbank. The building was heavily fortified with minefields and machine-gun positions. Germans suffered heavy losses trying to capture the structure and marked it as a “fortress” on their maps. The building was later famously renamed Pavlov’s House.

By the 27th of September, the Germans held control over the southern part of the city, slowly progressing through it by taking one position at a time, often with massive casualties. The Soviets controlled some northern and central parts of the city and critical crossing points across the Volga, which enabled a constant flow of fresh troops and supplies.

October city battles

After securing the southern part, German attacks shifted to the northern part of the city, where three giant factories were located: Red October Steel Factory, the Barrikady Arms Factory, and Stalingrad Tractor Factory. On the 10th of October, exceptionally intense shelling and bombing paved the way for the first German assault groups led by the 14th Panzer and 305th Infantry Divisions. The attackers managed to capture the Tractor Factory and made a breakthrough to the Volga, splitting the remnants of the 62nd Army in two.

By the end of October, Soviet defenders were in a helpless situation that worsened daily due to ice flows on the Volga, making it continuously harder to supply and reinforce them. Ferocious fighting continued throughout November, especially on the slopes of Mamayev Kurgan and inside the factory area in the northern parts of the city. By the end of November, the Soviets were split into two narrow pockets, holding only a tiny area on the western bank of the Volga.

Operation Uranus

As the bloody battle for the city continued through November, the Soviets were amassing an enormous concentration of manpower and equipment on the eastern banks of the Volga. They were preparing to launch a massive counterattack against the northern and southern German flanks. Soviet generals and , responsible for planning the attack, correctly identified that those positions were held by poorly equipped and less experienced Hungarian and Romanian Armies.

The Axis forces, consisting of German, Italian, Hungarian, and Romanian Armies, had neglected to consolidate their positions on the Don River, allowing the Soviets to retain their bridgeheads from which offensive operations could be quickly and easily launched. Due to the poor scouting by the German allies, the Soviet’s concentration of massive force had gone mostly unnoticed. At the same time, Germans poured more and more troops into Stalingrad and left their allies without almost any support from the rest of the German Army.

The Soviet’s plan involved quickly overwhelming the Hungarian and Romanian troops guarding the north and south flanks of the German Armies, enveloping the German 6th Army fighting in the city. Fifteen Soviet Armies had been planned to complete the operation – ten fields, one tank, and four air armies.

On the 19th of November, three Soviet Armies under the command of Nikolay Vatutin overran the Romanian 3rd Army holding the northern flank. The day after, two Soviet Armies overran the Romanian 4th Corps guarding the southern flank with an overwhelming number of tanks and manpower. Four days later, on the 23rd of November, the two attacking Armies met at the town of Kalach-on-Don, completely enveloping the German 6th Army and cutting their supply lines.

The encircled German Armies consisted of about 265.000 Germans, Romanians, Italians, and Croats in addition to 40.000 – 65.000 Hillswiliger (“volunteer auxiliaries”), a term Germans used for recruits among Soviet POWs and civilians from occupied areas. Those auxiliaries were initially used in supporting roles, but some also served on the front lines as their numbers and influence increased over time.

Even though the 6th Army was in a dire situation with no supply lines other than the Luftwaffe, Army Group A was still ordered to hold their positions in the Caucasus further south. On the 31st of December, they were ordered to retreat to avoid being trapped after the Soviets threatened to push on Rostov-on-Don.

As a response to the Soviet offensive and encirclement of the 6th Army, the German High Command formed Army Group Don under the command of Field Marshal . It consisted of twenty German divisions and two Romanian divisions in Stalingrad, divisions located on the Chir and Don Rivers, plus the remains of the Romanian 3rd Army.

The German Army chiefs pleaded to Hitler to order a breakout from Stalingrad and link with the rest of the Army Group Don, but both von Manstein and Goring convinced him that Army Group Don could break through the Soviet defenses and relieve the encircled army. At the same time, the Luftwaffe could transport enough supplies to the 6th Army to stay operational and continue fighting in the city.

In reality, there was no possibility of continuous supply by air. The Luftwaffe did not have enough transport capacity to deliver 750 tons of supplies per day to keep the 6th Army in fighting condition while only having one airport at Pitomnik. On the 27th of November, von Manstein, now aware of the situation, made a six-page report to the general staff in which he proposed that the Luftwaffe should supply the encircled army with only enough ammunition and fuel for a breakout attempt to link with the Army Group Don. Hitler dismissed the report and started preparing for a new German offensive to relieve the trapped army while the supply by air continued as planned.

The Luftwaffe severely lacked aircraft facilities, supplies, manpower, and enough aircraft for such a large operation. Initially, supply flights came from the airfield of Tatsinkaya, some 260km west of Stalingrad, but was overrun by the Soviets on the 24th of December. A new base was deployed at Salsk, some 300km away from Stalingrad, but had to be abandoned in mid-January for a rough facility at Zverevo. With airfields moving further and further from the 6th Army, winter weather conditions, technical failures, Soviet anti-aircraft fire, and fighter interceptions grounded more and more Luftwaffe forces. In total, the Luftwaffe lost 266 Junkers Ju 52s, 165 He 111 transport aircraft, 42 Ju 86s, 9Fw Condors, 5 He 177 bombers, and 1 Ju 290, along with approximately 1,000 highly experienced bomber crew personnel.

Operation Winter Storm

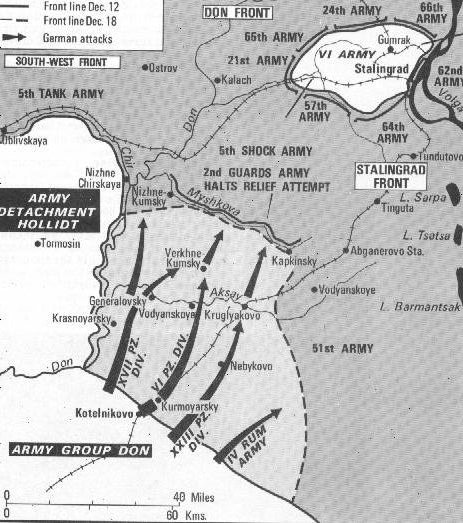

Von Manstein developed Operation Winter Storm with full consultation with Hitler’s headquarters. He planned to establish a corridor to the 6th Army to keep it supplied and reinforced to maintain its positions on the Volga. A further plan was drawn without Hitler’s knowledge – Operation Thunderclap, which included the subsequent breakout of the 6th Army and its incorporation into the Army Group Don.

Operation Winter Storm was initially planned as a two-pronged attack – one thrust would push from the area of Kotelnikovo (around 160km south of Stalingrad), while the second thrust would push from the Chir front (some 60km north of Stalingrad). General Zhukov had correctly predicted German plans and ordered continuous attacks on the Chir front, ruling out any possibility of the northern thrust.

Having no other options, the Germans decided to push only from the south with the 57th Panzer Corps consisting of two Romanian cavalry divisions and the 23rd Panzer Division supported by Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army. These units were not powerful enough to break the Soviet defenses, so the 6th Panzer Division was called from France to assist in the upcoming offense. On the 27th of November, the first trainloads arrived at Kotelnikovo station, immediately greeted with a “hail of shells” from the Soviet batteries and advancing infantry.

By the 18th of December, the relief forces were within 48km from Stalingrad, but the operation exposed the entire German Army Group South. German officers requested from the commander of the German 6th Army, , to defy Hitler’s orders and attempt a breakout, but he did not issue such an order. His primary concern was that, with the successful breakthrough of the 6th Army, the Soviets could attack the flanks of Army Group Don and Army Group B, resulting in the cutting off of the entire Army Group A still fighting in the Caucasus. The fact that the 6th Army only had fuel for a 30km push towards Hoth’s spearhead, which would not be enough for a complete breakthrough, also backed up Paulus’ decision.

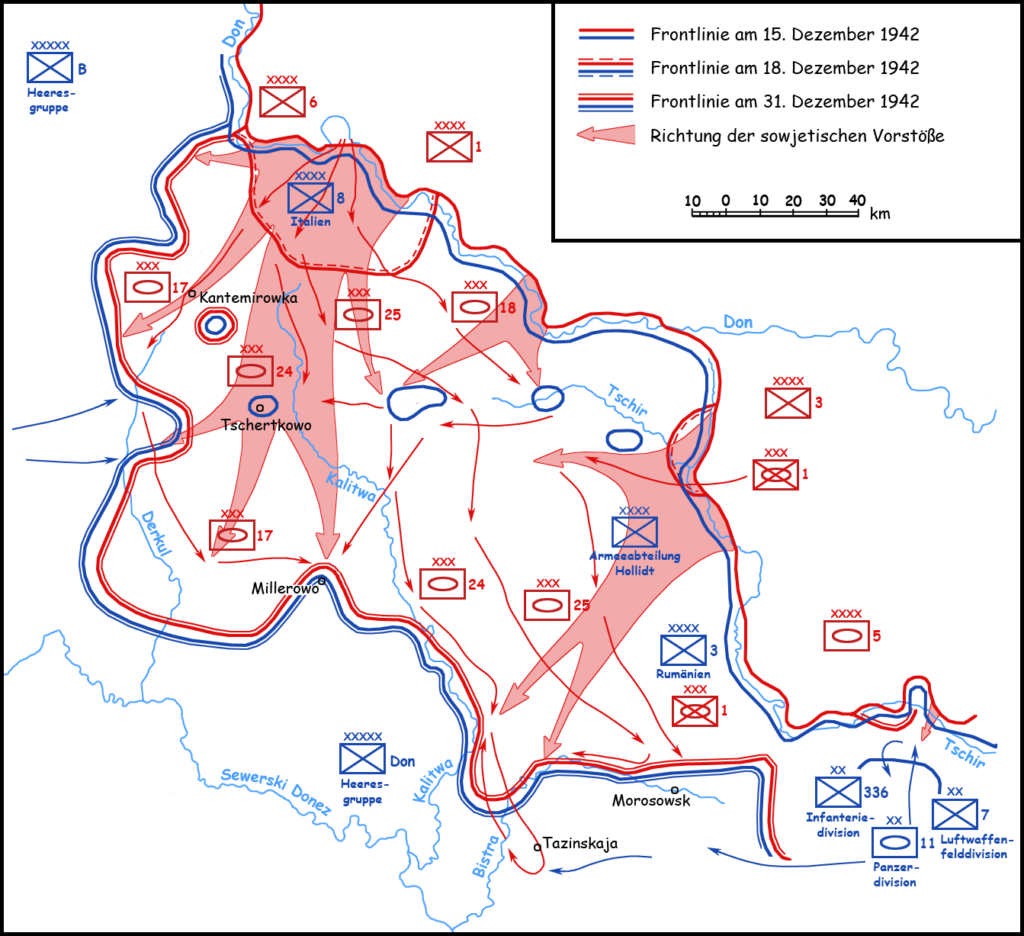

Operation Little Saturn

On the 16th of December, the Soviets launched Operation Little Saturn to break Axis defensive lines on the Don River, cutting off the German Army Group A in full retreat from the Caucasus. The attack was launched from the Soviet bridgehead at Marmon with 15 divisions supported by at least 100 tanks against the Italian Cosseria and Ravenna divisions. Initially, the Soviets faced stiff resistance, but on the 19th of December, they broke the defensive lines and pushed the Italians back.

Seeing that the Axis forces could not stop the Soviet advance, the Germans had to reevaluate the whole situation. On the 18th of December, von Manstein pleaded with Hitler again to order the breakout of the 6th Army, but Hitler refused. All attempts to relieve the trapped army were abandoned when Army Group A was ordered to pull back from supporting the forces in Stalingrad. With that order, the fate of the 6th Army was sealed.

On the 23rd of December, von Manstein’s forces switched to the defensive to deal with the continuous Soviet offensives. The only objective of the 6th Army was to hold for as long as possible, tying a significant number of Soviet forces in and around Stalingrad.

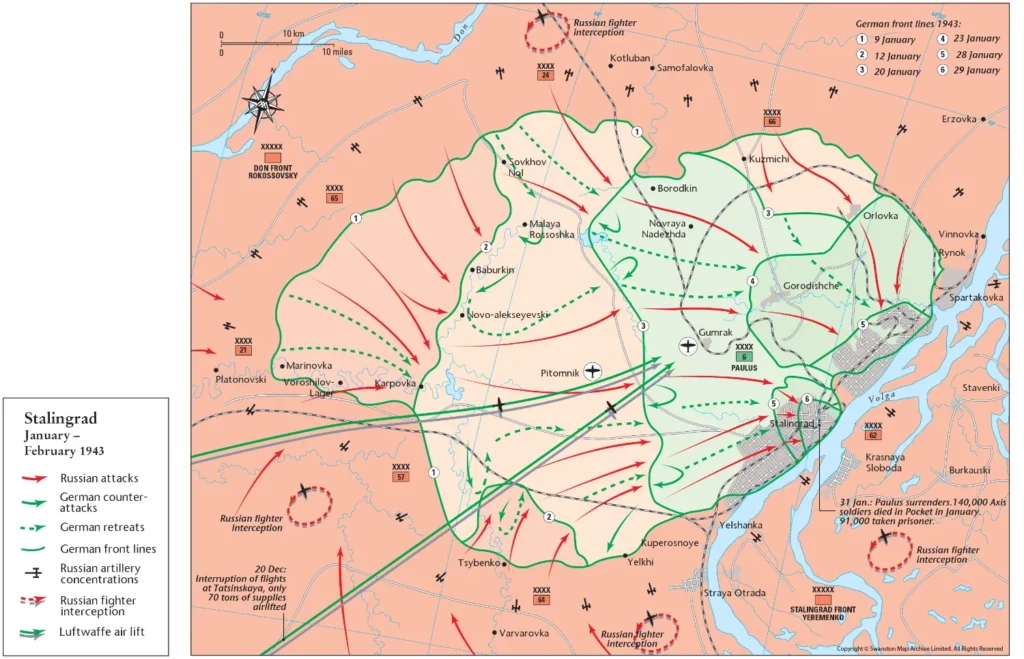

The end of fighting in Stalingrad

On the 7th of January 1943, the Soviets sent three envoys to deliver terms of surrender to Paulus signed by Colonel-General of Artillery and the commander-in-chief of the Don Front, Lieutenant-General . The terms offered were quite generous: if Paulus surrendered within the next 24 hours, he would be granted a guarantee of safety for all prisoners, medical care for sick and wounded, prisoners being allowed to keep their belongings, “normal” food rations and repatriation to any country they wished to after the war. Paulus requested permission to surrender, but Hitler refused, stating that “every day the army holds out longer helps the whole front and draws away the Russian divisions from it.”

Heavy fighting continued, pushing back German lines to the city itself. The loss of two operational airfields in the coming days meant an end to supply by air and evacuation of the wounded. After the 23rd of January, only sporadic air drops of ammunition and food were recorded.

The Germans resisted despite food and ammunition shortages, believing the Soviets would execute anyone who surrendered, especially Soviet citizens fighting for the Germans (“HiWis”). The Soviets were quite surprised when they realized how many German soldiers they trapped within the city and poured more troops into the fighting. Bloody urban warfare once again started in the city, much like in October and November, but this time in reverse roles – the Germans were on the defensive and slowly pushed to the banks of the Volga.

On the 22nd of January, Paulus was offered another chance to surrender, but Hitler again denied it, stating that there was no honor in surrender. He telegraphed Paulus, claiming they made a historic contribution to the greatest struggle in German history and that they should fight “to the last man and last bullet.” Paulus reported that he could no longer command his men, who were without ammunition and food, with about 18,000 wounded and sick.

On the 26th of January, the German forces were split into two pockets north and south of Mamayev Kurgan, with no telephone communication between them. The 8th Corps and 12th Corps held the northern pocket and the southern pocket by the 14th Panzer and 4th Corps. The estimated number of wounded and sick rose to 40,000 – 50,000.

On the 31st of January, read a proclamation that stated: “The heroic struggle of our soldiers on the Volga should be a warning for everybody to do the utmost for the struggle for Germany’s freedom and the future of our people, and thus in a wider sense for the maintenance of our entire continent.” In response to yet another request for surrender, Hitler promoted Paulus to Generalfieldmarschall, implicating that Paulus would shame himself if he surrendered by becoming the highest-ranking German officer ever to be allowed to be captured. Hitler believed that Paulus would fight to the last man or commit suicide.

On the same day, the Soviets attacked and captured the southern pocket headquarters where Paulus was located. Paulus claimed that he had been taken by surprise and did not surrender. He denied his command of the northern pocket and could not order their surrender.

On the same day, another pocket of German resistance, under the command of Heitz, surrendered. The northern pocket, the last pocket of German resistance under the command of Strecker, surrendered after his proclamation that his troops had done their duty and fought to the last man. Immediately after the surrender, Strecker sent a last radio message from Stalingrad stating that all fighting had stopped.

The Soviets took around 91,000 prisoners, with 22 generals. After hearing of Paulus’s surrender, Hitler was furious and said that he “could have freed himself from all sorrow and ascended into eternity and national immortality, but he prefers to go to Moscow.”

Casualties

The 5-month bloody battle for Stalingrad resulted in a staggering number of casualties on both sides, with the enormous loss of armament and materials.

The Axis losses:

- 747.000 – 868.000 total casualties:

- Over 600.000 Germans were killed, wounded, or captured (282.606 only in the 6th Army)

- estimated 110.000 – 160.000 Romanians (around 70.000 captured or missing)

- Estimated 114.000 Italians killed, wounded, or captured,

- estimated 105.000 – 145.000 Hungarians killed, wounded, or captured,

- estimated 20.000 – 50.000 Hiwis

- 900 aircraft

- 500 tanks

- 6.000 artillery pieces

The Soviet losses:

- 1.129.619. total casualties – 478.741 killed, 650.878 wounded or sick

- 4.341 tanks destroyed or damaged

- 15.728 artillery pieces

- 2.769 aircraft

It is estimated that around 235,000 Axis troops were captured during the battle. About 1,000,000 soldiers and civilians were killed.

Aftermath of the Battle of Stalingrad

The German public was unaware of the losing battle in Stalingrad to keep the morale and belief in Nazism ongoing. On the 31st of January, the German state could no longer hold a secret of the disaster in Stalingrad and broadcast an announcement of the defeat.

Some 11,000 German soldiers continued fighting in isolated pockets within the city through February and early March. They believed fighting would be better than slowly dying in the Soviet labor camps. The Soviets managed to capture some of the letters sent to their families in Germany in which they expressed belief in Germany’s ultimate victory, stating they were proud of their sacrifice to the Fuhrer. By early March, all fighting ceased, and all isolated pockets surrendered.

About 91,000 German prisoners were sent to prison camps and later to labor camps all over the Soviet Union on forced marches. Most prisoners died of wounds, disease, cold, overwork, mistreatment, and malnutrition. Only 5,000 returned to West Germany in 1955 after a plea by Konrad Adenauer.

Some German officers were sent to Moscow for interrogation and to be used for propaganda purposes. Paulus signed anti-Hitler statements shortly after his capture, which were broadcast to German troops. He remained in the Soviet Union until 1952 when he moved to Dresden in East Germany, where he defended his actions at Stalingrad, quoted as saying that Communism was the best hope for postwar Europe.

Significance of the battle

The defeat at Stalingrad was described as the greatest defeat in the history of the German Army and identified as a turning point in World War II. All German gains during Operation Case Blue had been wiped out. The German 6th Army had been destroyed. The forces of the German allies had been shattered. The Wehrmacht was in full retreat. The reputation of an invincible Army was gone.

Hearing news from Stalingrad demoralized the citizens of Germany. Even Hitler identified the significance of the defeat in his speech on the 9th of November, blaming Stalingrad for Germany’s inevitable and impending doom.

As for the Soviets, a major victory over an invading Army gave them much-needed confidence and belief in victory. A saying goes: “You cannot stop an army that has done Stalingrad.” Stalin was seen as a hero of the Soviet Union and was made a Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Commemoration

Stalingrad was awarded the title Hero City in 1945. A colossal monument called was built in 1967 on Mamayev Kurgan, the hill overlooking the city. It is part of a war memorial complex that includes the ruins of a Grain Silo and Pavlov’s House.

The first military parades were held in 2013 in Volgograd (Stalingrad), commemorating the 70th anniversary of the victory over the Germans.